Berkeleyan

For whom wedding bells toll — this time for keeps

Four years after their high-profile nuptials in San Francisco, lesbian and gay staff members are getting hitched again

![]()

| 17 July 2008

Jon Bain-Chekal and Mark Chekal-Bain pose with their son, Wesley. |

In May the California Supreme Court overturned a law limiting marriage to opposite-sex couples, opening the door for brides and brides (as well as grooms and grooms) to obtain marriage licenses in California.

It was the second time in recent years that gay couples in the Bay Area were granted official approval to get hitched. Four years ago, San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom ordered the city to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples, leading a number of gay campus staffers and their partners to brave rain and long lines to get one. Their licenses were nullified six months later, invalidating the marriages, but not before a number of lesbian and gay staff were featured in the Berkeleyan’s March 3, 2004, issue proclaiming their joy and solidarity.

To learn what the latest gay-marriage news might mean on the personal and political fronts, the Berkeleyan contacted the lesbian and gay staff it spoke with in 2004 — all of whom, we can report, were planning to get married once again.

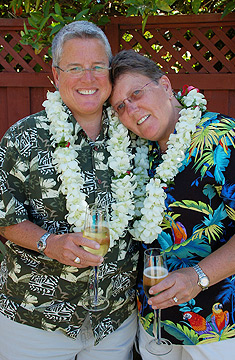

Joyce Jennings and Patty Mead re-tied the knot on June 24. |

The nullification was very frustrating, says Jon Bain-Chekal, finance project manager in the assistant controller’s office. His partner of 14 years, Mark Chekal-Bain, was then working for California’s attorney general, Bill Lockyer. “Technically, Mark’s boss annulled our marriage,” says Bain-Chekal. “Logically I knew the attorney general was just doing his job, but emotionally I was angry.”

Pamela Brown, an analytical-studies coordinator in the office of the vice chancellor for administration, recalls that when her marriage license was revoked, “it was like a punch in the gut.”

This month, Brown will again marry Shauna Rajkowski, who works for UC’s Office of the President. The couple, who have been together a dozen years, held a commitment ceremony seven years ago, then joined the throngs to wed at San Francisco City Hall in 2004. Since they announced their plans to wed in late July, Brown says, they’ve gotten a different reaction than they did when planning their commitment ceremony.

“People just get it. My mother is asking who’s going to walk who down the aisle, and we’re getting advice about the ceremony and what we should wear.”

Victoria Ortiz, dean of students at Berkeley Law, says that she and Jennifer Elrod, her partner of 22 years, still felt married in their hearts after their 2004 license’s annulment. “The sense of commitment and permanence was only enhanced,” she says.

When the women married again in June, the occasion was just as joyous as the earlier heady nuptials in San Francisco. The key difference was that this time around they had time to plan. Oritz and Elrod had wedding rings made to order, chose San Francisco District Attorney Kamala Harris to officiate, and penned words for the ceremony. “Because this time it is really legal, it did feel different,” says Ortiz.

Is two times the charm?

Four years ago, Patty Mead, an information-systems manager in Facilities and Spatial Data Integration, married Joyce Jennings, senior budget analyst in the office of the vice chancellor for administration. That first wedding “brought a sense of stability and a hunger for the real thing,” says Mead. Their son, who will be attending college this fall, thinks it’s about time that his mothers are permitted to marry, she says. “I think it’s a great way to send him off. It will allow him to participate in a groundbreaking activity that shows in a very direct way that change is possible.”

Pamela Brown and Shauna Rajkowski (top) are all smiles after getting their wedding license in Martinez. Jennifer Elrod, left, and Victoria Ortiz, right, were married by San Francisco District Attorney Kamala Harris last month. |

The 10-year-old daughter of another Cal couple, Charlotte Rubens, the Library’s head of Inter-Library Services, and Emilie Bergmann, professor of Spanish and Portuguese, will participate in their upcoming wedding ceremony. Four years ago, the couple left their child with friends while they waited five hours in the long San Francisco queue. “I think this time will be more real for her,” says Rubens, who has been with Bergmann for 35 years.

And while everyone the Berkeleyan spoke with found that getting married once more is an emotionally affecting experience, Margaret Chester, IST senior stores supervisor, echoes the other couples in her assessment of the ruling’s broader consequences: “The tax rights or benefits that we get won’t change.” Chester, a veteran, observes that her wife, Carol Cooper, won’t be entitled to her VA benefits should she die. “If our marriage was federally recognized, she would get that money as any other spouse would,” she says.

For Bain-Chekal, the recent ruling serves to highlight the ongoing struggle for equitable treatment. The bigotry of ultra-conservatives worries him less than the assumption that lesbian and gay couples living in the Bay Area no longer struggle for basic rights. “What many people forget is we are taxed differently, and policies are built around a singular notion of what makes up a family,” he says. For instance, he notes, UC policy doesn’t allow women or men who adopt children to use sick leave to care for their new family member. “Many institutions have more progressive parental-leave policies that don’t focus on the 1950s version of family,” he says.

Reading the tea leaves

Although conservatives have put an initiative on California’s November ballot to limit marriage to opposite-sex couples, antipathy to gay marriage is apparently not universal in those political precincts. When Margaret Chester called to tell her sister, a religious fundamentalist, about her upcoming wedding plans, her sibling wanted to know why she hadn’t gotten an invitation.

Margaret Chester and Carol Cooper got married in a small backyard ceremony. |

Brown, too, feels guardedly optimistic that attitudes toward gay marriage might be softening. When she and Rajkowski went to Martinez to get their wedding license recently, 70 supportive community members and clergy turned out at the Contra Costa County clerk’s office. Only three protesters showed up.

“The support for us and the right to marry is so different than it was four years ago,” says Brown, who is active in Marriage Equality USA, a group committed to securing the right to civil marriage for same-sex couples. “That’s why we’re very hopeful that when people start to see their neighbors getting married in their hometown that amendment won’t pass, and this issue will be over for the state of California.”

Rubens, who has lived through many chapters of the gay-rights struggle, hopes that “other states can see their way to pass similar laws and we can just normalize same-sex marriage, so that we can get on with other urgent business that our country needs to tend to.”