Berkeleyan

Concrete imagery

![]()

12 January 2005

|

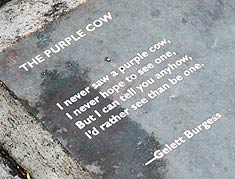

At the Berkeley Repertory Theatre event, Berkeley professor/poet Robert Hass, who selected the poems now displayed on 126 porcelain-enamel-and-cast-iron sidewalk panels, will read Addison Street verse and sign copies of The Addison Street Anthology: Berkeley’s Poetry Walk. He’ll be joined by some 40 poets featured in the book, from Opal Palmer Adisa to Dean Young.

| Sunday's event takes place at one of Addison Street’s main- stay institutions, the Berkeley Repertory Theatre (Thrust Stage); it is free and open to the public. Click here for information on the anthology, a paperback that retails for $14.95. |

The Addison Street Anthology, published by Berkeley-based Heyday Press, enriches that process of discovery. In its pages, Hass (a former U.S. poet laureate) and poet/faculty member Jessica Fisher complement each poem, translation, or song lyric included on the walk with notes that provide its biographical, literary, and historical background. Each of the block’s poets have, in some way, a connection with local history: Most were born, lived, or worked in the East Bay; a few (Robinson Jeffers and George Oppen among them) Hass deemed essential to the development of poetry in California.

|

A sampling of Addison Street poems, along with excerpts from commentary provided in the companion book, appears below.

— Cathy Cockrell

(Photos by Deborah Stalford)

The Want Bone by Robert Pinsky

The tongue of the waves tolled in the earth’s bell.

Blue rippled and soaked in the fire of blue.

The dried mouthbones of a shark in the hot swale

Gaped on nothing but sand on either side.

The bone tasted of nothing and smelled of nothing.

A scalded toothless harp, uncrushed, unstrung.

The joined arcs made the shape of birth and craving

And the welded-open shape kept mouthing O.

Ossified cords held the corners together

In groined spirals pleated like a summer dress.

But where was the limber grin, the gash of pleasure?

Infinitesimal mouths bore it away,

The beach scrubbed and etched and pickled it clean.

But O I love you it sings, my little country

My food my parent my child I want you my own

My flower my fin my life my lightness my O.

Robert Pinsky came to UC Berkeley in the early 1980s as a professor of English, and for a decade was an influential teacher of young poets here. During his Berkeley years he published three volumes of poetry: History of My Heart, Poetry and the World, and The Want Bone. In 1990 he took a position at Boston University. Pinsky served as poet laureate of the U.S. from 1997 to 2000.

from Cold Mountain Poems by Han Shan,

translated by Gary Snyder

The path to Han-shan’s place is laughable,

A path, but no signs of cart or horse.

Converging gorges — hard to trace their twists

Jumbled cliffs — unbelievably rugged.

A thousand grasses bend with dew,

A hill of pines hums in the wind.

And now I’ve lost the shortcut home,

Body asking shadow, how do you keep up?

Han Shan, whose name means “Cold Mountain,” was a famed Buddhist poet and recluse of the T’ang dynasty (618–907). His work reflects an outsider tradition in classical Chinese and Japanese poetry. Poet Gary Snyder began these translations while studying at Berkeley with the great T’ang scholar Edward Schaeffer. A fictionalized account of Snyder’s discovery of Han Shan is recorded in Jack Kerouac’s book The Dharma Bums.

The Unswept by Sharon Olds

Broken bay leaf. Olive pit.

Crab leg. Claw. Crayfish armor.

Whelk shell. Mussell shell. Dogwinkle. Snail.

Wishbone tossed unwished on. Test

of sea urchin. Chicken foot.

Wrasse skeleton. Hen head

— eye shut, beak open

as if singing in the dark. Laid down in tiny

tiles, by the rhyparographer,

each scrap has a shadow, — each shadow cast

by a different light. Permanently fresh

husks of the feast! When the guest has gone,

the morsels dropped on the floor are left

as food for the dead — O my characters,

my imagined, here are some fancies of crumbs

from under love’s table.

Sharon Olds was born in San Francisco in 1942 and grew up in Berkeley; she attended Berkeley High and Stanford University. She is the author of a number of books of poetry, including a National Book Critics Circle Award-winner, The Dead and the Living.

Dying In by Peter Dale Scott

dying on the grass

in front of the chancellor’s building

for Charlie Schwartz’s anti-weapons protest

brings back confused

memories of the wartime sixties

hitting the dirt before we realized

these were just wooden bullets

and then walking back through tear gas

to teach a class

lying here

and watching the neutral passers-by

scale the vertical asphalt

I feel neither

the old embarrassment at being

at right angles to most people

with brief-cases

nor, and this is the spooky part

that steam of comprehending anger

only the warm

smell of the grass beside my nose

saying, come back here every now and then

Montreal-born Peter Dale Scott came to UC Berkeley in 1961, where he taught in the speech and English departments. In addition to poems — including a trilogy about private life and political violence in the 20th century — he wrote studies of the CIA’s involvement in the cocaine trade and of the assassination of John F. Kennedy. He was active in the ’60s anitwar movement.

Hey, fog, go home.

Go home, fog.

Pelican is beating your wife.

This Ohlone song was gathered by UC Berkeley anthropologist Alfred Kroeber in Monterey in 1909. His informants were Maria Viviana Soto, who was then 78, and her niece, Jacinta Gonzales. The wax cylinders on which these songs were recorded are in the Hearst Museum of Anthropology. Both women died in the influenza epidemic of 1916-17.