Berkeleyan

A career spent unearthing ancient history

On the threshold of retirement, classical archaeologist Stephen Miller looks back at the struggles, surprises, and thrills of 33 years of excavations in Nemea, Greece

![]()

08 December 2004

On Dec. 31, Stephen Miller, professor of classical archaeology and director of Berkeleyís excavations in Ancient Nemea, Greece, will retire after a remarkable campus career that began in 1973. Miller, 62, has made headlines worldwide for his work uncovering an ancient athletic site where Panhellenic games were held. He also helped establish the New Nemean Games ó international footraces, open to all, now held at the ancient site every four years.

On Tuesday, Miller gave his 33rd and last Nemea Lecture, an annual update on his work for hundreds of donors and faithful followers of the project. UC Berkeley Public Affairs recently asked Miller to reflect on the past three decades and look ahead to a retirement that will include living in both Berkeley and Greece with his wife, Effie; working as acting director of the excavation site until June 30; continuing his scholarly work on the artifacts unearthed at Nemea; and occasionally returning to campus to teach.

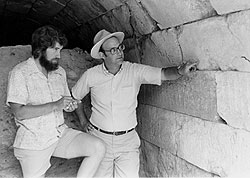

When you started the excavation at Nemea, did you ever imagine you would make headline-grabbing finds?

In the early days at Nemea, Miller and a grad student examine graffiti etched by ancient athletes in the vaulted tunnel that leads to the stadium, constructed in 330 B.C. One inscription reads ďAkrotatos kalos,Ē or "Akrotatos is beautiful." A later scribe added, ďtou gracantos,Ē or "to the guy who wrote it." The tagging from antiquity gives a rare insight into the human side of the ancient Panhellenic games.

No. Frankly, I did not want headline-grabbing finds. I didnít want gold statues, because of the jealousies that would come [from other archaeologists]. I wanted discoveries that made a difference in what we understood about the history of ancient Greece, the architecture, ancient athletics.

When the big discoveries did come, did it surprise you?

Listen, it is a surprise every time a crummy potsherd comes out of the ground. Do you know what it means to be the first person in 2,000 years to touch something your ancestors have made, to touch that coin or that stone and know that some ancient mason worked on it, smoothed it down, carved the relief thatís seen there? That thrill never leaves.

What were the biggest challenges you faced in Nemea?

Money. And then there was money. And there was money. I suppose in academia we are always complaining about money, but the fact is Iíve raised almost every penny that has gone into Nemea from private donors, and thatís taken a lot of time and a lot of energy. But the donors over the years have become devotees of Nemea, which means theyíve become my students and part of my extended classroom. I feel that I have fulfilled a part of my pedagogical mission at this university with my donors.

How has your work had an impact on the people of Nemea?

I know the project had an impact in one major way, and that was social. When I arrived, there were 300 people in the village, and they were divided into two groups: the rich and the poor. The rich were the big landowners, and the poor worked for the rich at their beck and call. There were two families who ruled the roost. There was no external law enforcement, just these families who were the arbiters.

I upset the village very badly. The people who had always been the hired hands of these families all of a sudden had other work [digging for the excavation] four or five months a year. They had more income, which meant that they were independent. So youíd hear things in the coffeehouse like, ďThereís that old shepherd whoís sending his daughter off to nursing school. Who does he think he is? Itís Millerís fault. Heís given him airs because he works for the excavation.Ē

And didnít you have some dangerous situations as a result?

I was shot at once. In 1980, I was sitting at my desk, and a shot rang out, and I heard what I thought was a mosquito going by my ear. I took a nosedive to the floor. By the time the police got there from the next village five miles away, there was nobody to be seen . . . Ultimately the chief of police went to one [suspected] family and said, ďIf Miller gets run over by a bus in Berkeley, Iím coming after you.Ē And that stopped it.

It was very much a social upheaval, which may have come anyway as a result of how Greece was advancing, but I was the flashpoint for that in the village of Nemea. Things have changed now. I am not anymore an agent of change. I am part of the establishment, and there is an archaeological site. . . . And last year we had more than 28,000 people visit the site. And the villagers see that happen and see the jobs it creates, and a sense of self-esteem and status comes with that.

What was your most exciting moment at Nemea?

Stephen Miller in 1995, amid the campus collection of statuary that he and his students helped preserve.(Ben Ailes photo)

There are two. The first was in 1978, when we discovered the tunnel leading into the stadium. When we proved that the Greeks, as of the period of Alexander the Great, knew how to build the arch and vault. The next day, we found graffiti [scrawled by ancient athletes] on the walls of the tunnel and began to get real insight into the human side of Greek athletics. And that thrill hasnít worn off ó every time I walk through that tunnel I get goosebumps.

The second moment was in 1996, standing on the track during the first revival of the Nemean Games, when I heard [runnersí] footsteps on the track surface that I had uncovered, saw people running down the track and heard people shouting, and the place came to life.

And particularly when running down the track were a fellow named Chang-Lin Tien, former Athletic Director John Kasser, the director of the Fulbright Foundation in Greece, the American and Czech ambassadors to Greece, an Athenian lawyer, a cop from a local village, a farmer from our village, and a couple of others. They are all dressed in chitons (tunics), they all have bare feet, and somebody standing next to me said, ďI thought the chancellor was going to be in this race ó which one is he?Ē And the light bulb went on. We have asked ourselves for a long time where democracy came from, and from that point I began to work on the theory that it was against the background of naked athletes that the concept of equality before the law, which leads to democracy, was born in Greece.

What are the challenges of working in two cultures?

What challenge? There is no challenge. Do you know what is so wonderful about my life? I never get bored. I donít have a chance. Just about the time I get sick and tired of the situation here, I leave Berzerkeley and go to little funky Nemea. Just about the time that I get hungry for baseball, I come back in time for the World Series.

What are your immediate plans after you retire?

Miller in a local warehouse last year, where his classics grad students continued painstaking work to repair and restore the collection of plaster casts. (Bonnie Azab Powell photo)

To go to Nemea right away, on Dec. 22 . . . to start construction on our house outside the village, with the whole valley at our feet. [The house will include] my library, a couple thousand volumes. The idea is this becomes a research center, of which the museum at Nemea would be one a part. This house and collection will eventually come to the university.

Is it true youíll be leading a Bear Treks trip to Libya?

Iím going in March. It is something Iím really looking forward to. By the time I started in the profession, Libya had become closed, and both the Greek and Roman antiquities, of which there are extensive examples there, were off-limits to Americans. Suddenly, itís possible to go and look at these things. Trips like this are necessarily very quick and superficial, but itís still more contact than I ever thought Iíd get with the antiquities in Libya.

What discoveries do you hope will be made in Nemea in the coming years?

Iím absolutely certain the rest of the early stadium will be found. One of the ironies of my profession is that we have the great literature of ancient Greece, but the architectural settings of that literature have not survived to us. . . . Weíve got the poetry of Pindar and Bacchylides celebrating the victories at Olympia and Nemea, but the earliest stadium we possess is 100 to 150 years later than those poets. At Nemea, weíre [discovering] the stadium that existed at the time that they were writing their poems.

Also, the hippodrome [for horse racing] is there. Iím convinced of it. Iím expecting my successor, whoever that person is, to prove that Iím right.

We also know there was a sacred road that tied the stadium and Temple of Zeus together. . . . In 1997, a trench was put in between those two structures for an aqueduct ó in the digging, they came upon a large wall, almost three feet thick, with a lot of 4th century B.C. pottery in it. We donít know what this building is, but it has to be an important structure that had to do with the functioning of the Nemean Games. And that awaits my successor.

In addition to your work in Greece, youíve made important finds here on campus, right?

The big find, the big surprise, the thrill, was the portrait of Plato that had languished in the basement of the Hearst Gymnasium for generations. And it had [mistakenly] been judged to be a fake. . . . Here, all of sudden, Iíd discovered the best-preserved portrait of Plato from antiquity.

Also, Phoebe Hearst gave to the university over 300 plaster casts of Greek and Roman sculpture, with the notion that this would be part of a collection where citizens of California could study the great cultures of the world. These were on display until at least 1915 ó in the 1930s, they went under the bleachers of Edwards Field. When I arrived on campus in 1973, we found these casts broken, dirty, eroded away [from being stored under] the bleachers above, covered with bird droppings. We whisked them off. . . . and students got the feeling for sculpture as 3-D figures.

What are your thoughts about your career at Berkeley?

This university said to me 33 years ago, ďHereís enough rope, letís see if you can keep from hanging yourself ó and if you do, thatís OK.Ē There was a trust. There was a belief that if they would support me, I could do something that I think is a little special. There arenít many universities that would have done that. I donít think there are many universities that would have had three chancellors, a vice provost, an assistant chancellor, and assorted faculty and staff members come, take off their clothes, put on tunics, and run on the track ó not caring about their pride and dignity, but being curious about learning.

For more on Stephen Millerís work at Nemea, see www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2004/03/30_nemea.shtml, or go to newscenter.berkeley.edu and search for ďNemea.Ē