![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Bionic Chip

Merges Living Biological Cell With Electronic

Circuitry

By Kathleen

Scalise, Public Affairs

Posted March 1, 2000

|

|

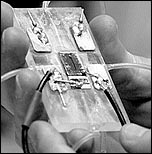

The

"bionic chip" features a living biological cell

successfully merged with chip electronic circuitry

for first time. The tiny cell, invisible to the

naked eye, sits in a hole in the center of this

chip. It is kept alive with an infusion of

nutrients through the clear tubes. Red and black

wires are part of the chip circuitry, the chip is

mounted on a plastic slab making it large enough to

hold.. Boris Rubinsky and Yong Huang photo |

|

|

The new chip gives scientists something they long have sought: an "open sesame" tool to get safely inside fragile, living cells at the touch of a button.

The discovery is an example of the type of research the campus is sponsoring through the Health Sciences Initiative, an effort that draws scientists from both the physical and biological sciences into a multidisciplinary search for solutions to today's major health problems.

"It's a key discovery because it's the first step to building complex circuitry that incorporates the living cell," said mechanical engineering Professor Boris Rubinsky, who created the device with graduate student Yong Huang. Such chips and the elaborate bionic circuitry they might make possible could be useful for developing body implants for treatment of genetic diseases.

The new chip uses the discovery that a biological cell can act in a circuit as an electrical diode, or switch, that allows current to flow through the device at certain voltages.

"It works this way: the biological cell does not transfer any current until a

particular voltage is reached," said Rubinsky. "At that point, when the right voltage is attained, pores open in the cell membrane and current starts to flow through the cell."

The particular voltage necessary to trigger the cell diode is different for each type of cell. The new bionic chip automatically determines the right voltage and, once known, "it's like having the remote control to a door," he said. "This is important because the door to the living cell has been very important but very difficult for us to open reliably until now without causing any damage to the tissue."

Cell membranes allow certain materials in and keep others out depending on the needs of the cell. The bionic chip can open and close a cell membrane in milliseconds, allowing for a very precise control never before possible. Once in place in the circuit, the cells themselves are considered bionic since they can be operated in this way by computer control.

"We can introduce DNA, extract proteins, administer medicines -- all without bothering other kinds of cells that might be around," Rubinsky said.

Living tissue has long been known to pass current, he said, but until now, no one knew it could sit on an electronic chip and act as a diode.

"In the past, any electricity applied to the cell was like hitting it with a hammer in the hopes that something would happen or it would open for us. Now, we know just how to make it work," Rubinsky said.

Berkeley's bionic chip took three years to build using silicon microfabrication technology. It is transparent, so it can be studied by microscope, and measures about one hundredth of an inch across. The much tinier cell, which measures about 20 microns across, or one thousandth of an inch, is not visible to the naked eye. It sits in a hole in the center of the chip and is kept alive with an infusion of nutrients.

Applications for the bionic chip are varied and potentially include new ways to treat genetic diseases such as cystic fibrosis or diabetes, safer methods to test new pharmaceuticals for side effects and more complex bionic electronic circuitry.

"The first electronic diode made it possible to have the computer," Rubinsky said. "Who knows what the first biological diode will make possible?"

He said first commercial applications could begin within the year.

The first report of the technology is in the February issue of the journal Biomedical Microdevices. Berkeley applied for a patent on the technology last summer and is in the process of licensing it commercially. The work was funded by a Chancellor's Professorship award.

![]()

![]()

March 1-7, 2000

(Volume 28, Number 23)

Copyright 2000, The Regents of the University of

California.

Produced and maintained by the Office

of Public Affairs

at UC

Berkeley.

Comments? E-mail berkeleyan@pa.urel.berkeley.edu.